By Nathan Starnes

It was the English concept of ‘Been to America’ that caused Environmental Scientist Advisor John Walker to think about leaving Britain many years ago.

While researching infectious diseases at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom in 1998, Walker followed a well-beaten path as he made the decision to do his post-doctoral research in the U.S.

“After finishing your Ph.D., you go abroad.” Walker explained. But “I never intended to stay.”

That was 36 years ago, and now, well established with a career and family, and as a newly minted U.S. citizen, he goes back only to visit.

His journey landed him in Memphis to do post-doc research with a scientist who had a connection to his Ph.D. mentor.

“I didn’t know anything about Memphis, Tennessee except it was the home of Elvis,” Walker said. “You can imagine that coming from Britain to Memphis, I might as well have been dropped in the Gobi Desert. There was no soccer, no cricket, no English folk music, no real beer.”

But he found some common footing underground – and in the darkest of places – found love.

A scientist who was a member of the Cave Research Foundation at Mammoth Cave suggested Walker join the group. As he’d done some caving back home, Walker thought that this was his chance to experience life outside of Memphis.

He and another caver, Roberta Burnes, were assigned by a Welsh-American couple who were members of the foundation to do extensive mapping trips, documenting the cave’s passages. The couple would later confess they’d intentionally navigated Walker into proximity with Burnes, an Environmental Scientist Advisor, who works in the Division for Air Quality.

“When you spend 12 to 13 hours underground with someone it can go one way or the other,” Walker said. “I ran compass and Roberta was the cartographer. We only found out about their plan later.”

Burnes was living in Cincinnati, Walker said, while he was in Memphis. Their paths intersected again and again through caving trips in Kentucky and would later intersect again when she had a job interview in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

The course plotted by the Welsh-American couple was fruitful. Walker and Burnes married in 1991 and soon after, moved to Kentucky.

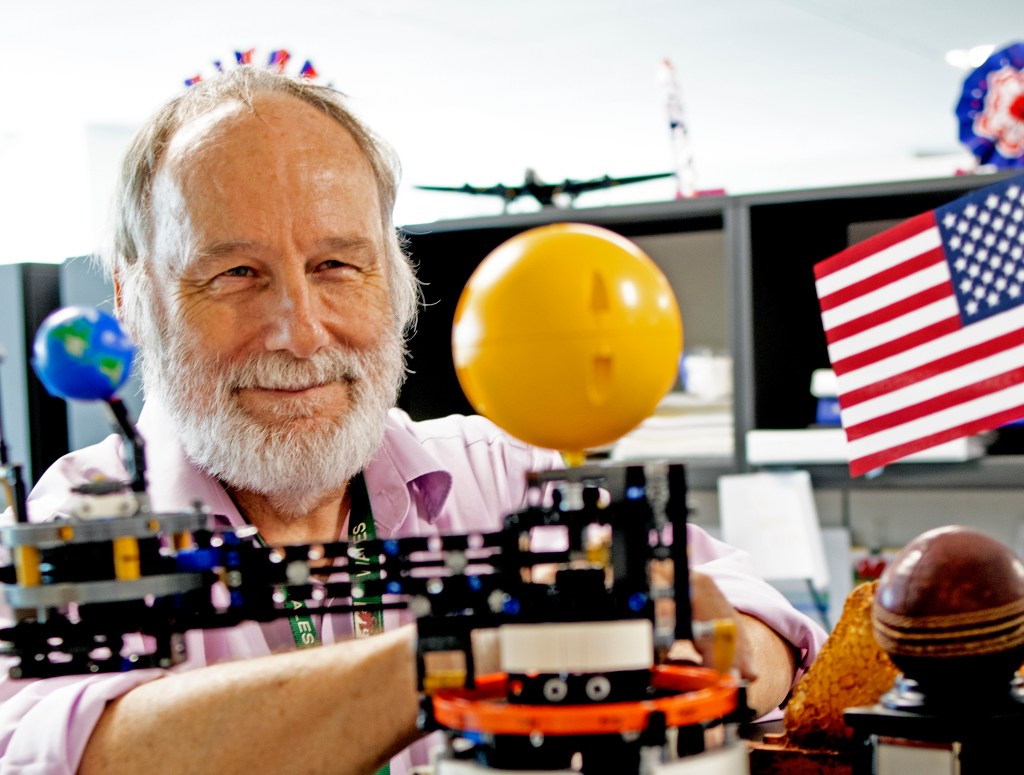

Hired in DAQ’s permit support section in 2015, Walker later moved to do quality assurance for air monitoring data as well as working on the calibration and certifications of air monitoring stations around the state.

After that, he took the opportunity to train wastewater and drinking water operators in what was then the Division for Compliance Assistance. The Covid Pandemic created an opportunity to hold classes online for a merged Division for Enforcement, where he now assists with data analysis.

His love of sports made him a fan of Wrexham AFC and Manchester Utd. soccer, even if it now is difficult for him to catch their matches on American television.

After keeping bees, and making his own mead, Walker thought he could make his own beer. His brews now find their way to regional contests, where he enjoys the company and competition of other local brewers. Not one to brag, his bottles have taken home medals.

His favorite type to brew is known as a Grisette, a wheat beer traditionally brewed in the mining area in South Belgium. He discovered the style during a trip to Seattle, and on return, mentioned it to local breweries who claimed they would never brew the style. Walker hopes to change their opinion.

“I am now on batch #6, trying to tweak the recipe.” Walker said. “I did brew a test batch for Blue Stallion in Lexington, and it was well received. Crushable as they say.”

Walker said there are a lot of similarities between Kentucky and Wales. “I was raised in a coal mining village, and I worked in a steel factory during the summertime when I was a college student.

But after raising a family, Kentucky has become home to him. And after three decades, he felt called to become a citizen.

“A lot of it is, you know, I’m old,” Walker said. “Social Security is an issue, potentially. I had to make sure financially, things were secure. Being a citizen means that the security is there.”

About 800,000 people undergo the naturalization process each year taking about six to eight months to complete the journey. For some, they may have to try over and over until they get accepted for an interview or until they pass all portions of the test.

For Walker, however, his journey was a bit more unique.

The whole process took only three months, from March to June of this year. Due to his British background and his English-speaking, no reading and writing test was administered. After an interview, a civics test, and a naturalization ceremony, where he took the Oath of Allegiance, Walker was able to call himself an American citizen.

While he will vote and exercise his duty to vote after all these years of being a spectator of the American democratic process, he welcomes the challenges and work that he believes comes with being a citizen.

“There’s an obligation to try and make where you live better than it was,” he said. “As a resident of Kentucky, I have that responsibility. Now as a citizen, within the powers and opportunities I have as a citizen I have that responsibility and duty.”

Walker is a cofounder of GleanKY, a nonprofit that provides fresh produce to thousands of people across Kentucky, using volunteers to gather excess produce from farms, orchards, farmers’ markets, grocery stores and supermarkets.

According to GleanKY’s most recent totals, it has gleaned nearly 3 million pounds of produce since they were founded in 2010. In it’s 2010 annual report , it had distributed food worth more than a staggering $3 million and prevented more than 281 metric tons of carbon emissions.