By Brad Bowman

Remote Kentucky wetlands with a delicate balance of open canopy and the right amount of saturated soil create the perfect habitat for an almost other worldly flower – the white fringeless orchid.

The federally threatened species is bone white with blooms that make it glow against its green surroundings.

Unlike other plants, the white fringeless orchid requires specific habitat conditions. So, a crucial part of the puzzle for the orchid’s success requires restoring native wetlands.

Unfortunately, about 80 percent of native wetlands have been altered – drained for development or farming, destroyed by invasive species, or overtaken by trees in areas where pine stands may have once periodically burned.

Frequent clearing of these areas prevents trees like yellow poplar and maple from creating a larger canopy, robbing the orchid of needed sunlight and balanced moisture.

The Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves (OKNP) is working to preserve and restore the delicate flower. Earlier this year, the OKNP introduced a new orchid colony in the southeastern part of the state.

“We work on the conservation of several native orchids. This is one of the rarest,” said Tara Littlefield, biological assessment and conservation branch manager. “Orchids in general are my favorite group of plants to study because of their unique relationships with pollinators, fungi, and their habitats.”

Littlefield conducts research related to the white fringeless orchid population and ecology for her doctoral degree with the University of Kentucky. She leads the OKNP’s projects specific to orchids and works with biologists, researchers and land managers in Kentucky and across the orchid’s range to research the flower’s habitat and pollinators, and to restore, monitor, and manage colonies.

“Restoring these wetlands involves removing young trees and shrubs, conducting prescribed fire, and even acting like beavers by creating debris dams. It’s really rewarding to watch the species’ diversity and population size increase in our restoration sites. The orchids, pollinators and so many other rare species benefit from these efforts.,” Littlefield said.

She noted collaborations with Dr. Christopher Barton and the University of Kentucky have been central to restoring wetland habitats that support the orchid. “Since 2009, we have jointly restored a population on a state nature preserve in Pulaski County, where monitoring has documented gains in both orchid abundance, floristic quality and pollinators. These efforts now extend, in partnership with the Daniel Boone National Forest, to all known Kentucky populations.”

The white fringeless orchid grows in the southeastern region of the United States. Kentucky is the most northern point of its range. The OKNP, the USDA Forest Service and scientists with the University of Kentucky help manage 10 areas in the state where the federally endangered orchid still occurs, and this year new colonies have been established in restored wetlands.

This type of work is both personally and professionally rewarding for Forest Botanist David Taylor with the USDA Forest Service. “Professionally, the satisfaction is knowing that the USDA Forest Service is meeting one of its many missions — working to recover a rare species,” Taylor said. “Personally, this orchid is beautiful and knowing that today’s work will help to keep the plant on the landscape to be enjoyed in future years is satisfying.”

The orchid wetlands, Taylor said, are small, tiny treasures in the context of the greater forest habitat of the Commonwealth. They are easily forgotten, and almost as easily overlooked.

“Improving habitat in these areas helps maintain the limited available habitat for several rare species, including the white fringeless orchid,” Taylor said. “Projects like this maintain the uncommon wealth in the state.”

For the newly established site, the orchids were grown from dust-like seed collected in Kentucky.

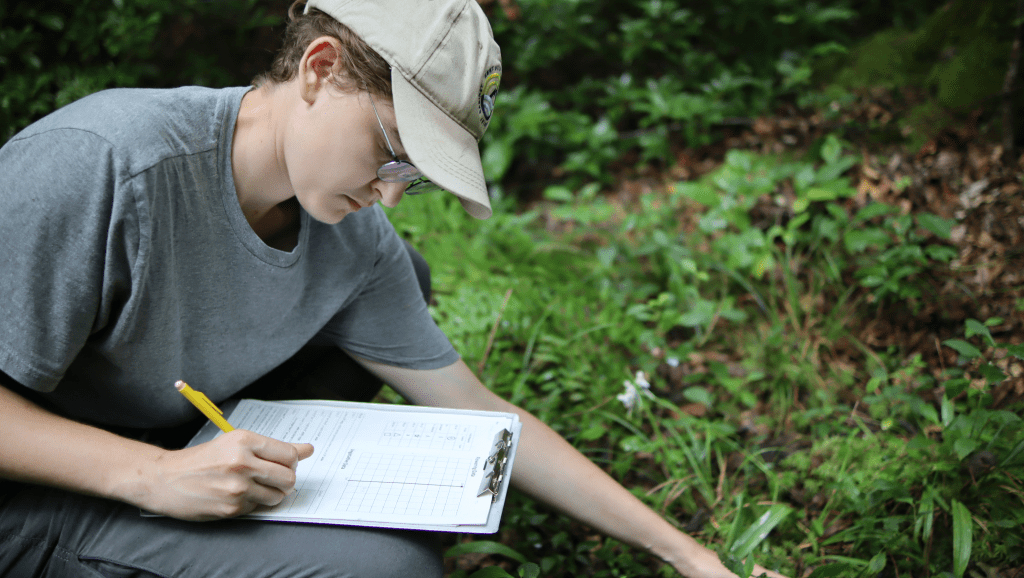

OKNP staff heavily document and monitor the sites for surrounding plant and insect life, the density of the canopy and surrounding trees, the vegetative orchids versus the flowering ones, the soil temperature and moisture content, the associated pollinators and pests, and how a plot has evolved. All to measure and correlate the survivability of the flower.

“We started this project by looking at the leaf sizes of the orchids and classify them in their rough age groups, to see if there were new seedlings coming up,” Rachel Cook, a botanist with OKNP said. “The goal is to manage hydrology, increase the orchid population with increased light, and map the flowers to see the differences year to year.”

The older the orchid, typically older than two years, the more probable it will flower and produce seeds. The white fringeless orchid typically blooms from late July to early September.

Categories: All, EEC's Blog, Environmental Protection, Featured, Media Gallery, Nature Preserves, Sustainability