BY AIDAN DILLARD-HIJIKATA

In the past 20 years, our risk of lead exposure has decreased dramatically. Lead is no longer used in wall paint, cups, gasoline and medicines. Most lead water service lines and household pipes have been replaced with less toxic materials. In 1986, the federal government essentially banned the use of lead materials in water and plumbing systems with the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act amendments.

Today, most of the potential risk for lead contamination in water comes from inside a building, from older faucets, spigots and other fixtures.

Minimizing the risk of lead contamination in drinking water is an ongoing effort among state and federal government agencies, particularly in facilities that care for our youngest citizens. According to the Centers for Disease Control, even low levels of lead in blood is associated with developmental delays, difficulty learning, and behavioral issues, and children six and under are at greatest risk.

The Kentucky Division of Water, through the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN Act) grant program, has been partnering with the Kentucky Rural Water Association (KRWA) to test the water in schools and childcare facilities for lead. Participation is voluntary and non-punitive and is seen as an educational opportunity for participants.

“We help interpret results, identify if issues are fixture-specific or building-wide, and guide next steps,” Division of Water Environmental Scientist Advisor Eileen Miller said. “Private testing offers a faster turnaround, sure, but our program is comprehensive and free.”

Although Kentucky’s program has been around since 2020, it has begun to gain traction in recent months, partly due to funds made available through the EPA’s Water Infrastructure Improvement for the Nation (WIIN) grant. Grant funds totaling $1.9 million in Kentucky provide free testing for schools and childcare facilities and could be used to help remedy issues found with fixtures.

So far, KRWA has collected samples from 120 schools and childcare facilities, Miller said, which are analyzed for lead at the state’s lab in Frankfort. Another 30 facilities have registered for the program and are to be tested within the next couple of months.

So far, results have been good. Of the outlets tested, 78 percent have shown levels below one part per billion (ppb).

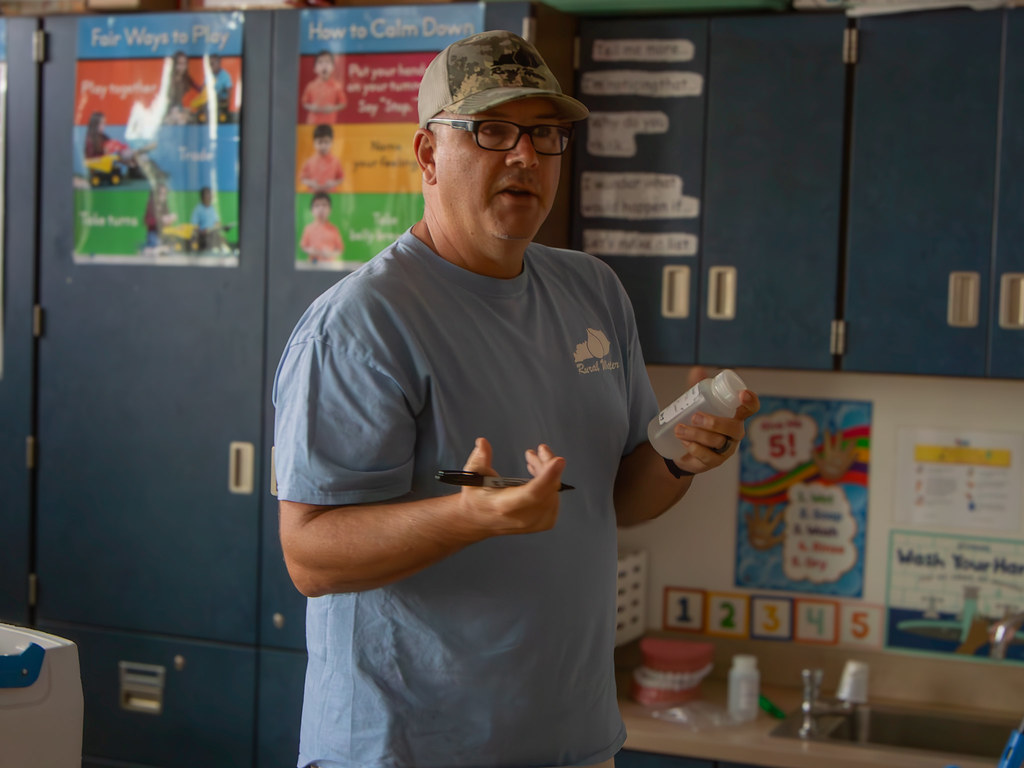

Although the EPA has set the new action level at 10 ppb under the Lead and Copper Rule, “the Division of Water and KRWA are pushing for 1 ppb,” said Todd Ritter, one of four KRWA staff members who travel across the Commonwealth to collect water samples for the program. That number is very close to the minimum amount that can be detected by modern equipment, he explained.

If testing shows higher levels of lead are present, the focus shifts to providing guidance and support to remedy the issue.

When detections occur, Ritter said, KWRA recommends flushing the water lines for 30 seconds before using the water. In some instances, schools may elect to replace fixtures, such as old drinking fountains, if they are suspected of being a source of lead contamination.

“Older buildings tend to be more vulnerable,” Ritter said.

Under EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI), local water systems will be required to offer lead testing for drinking water at elementary schools and childcare facilities beginning in 2028. Until then, Kentucky’s Voluntary Lead Testing program is providing an essential, immediate service for many schools that want to know the quality of their drinking water.